Introduction

How do you know what something is? How do we know if something is something and not something else? What is a thing?

Thousands of years after philosophers began to define the world around us, we still seek to explain and contextualize our lives and the places in which we live them. In recent decades, this process of definition involves massive amounts of data across dozens of information systems. These systems contain hundreds of representations: people, organizations, human and physical processes, and many more things. Ergo, the need to consolidate trillions of records across information systems is paramount for understanding the world of things around us: how representations are captured and how people make decisions based on these representations.

What follows is my experience thus far with these challenges and a few lessons learned from using an upper- or top-level ontology to structure and consolidate knowledge for machine learning.

Note: I interchangeably use upper-level ontology (ULO) and top-level ontology (TLO). ISO refers to Basic Formal Ontology (BFO) as a TLO, but BFO's official book refers to itself as a ULO. So for this blog post, they are the same thing.

Of Machine Minds And Human Madness

Back to the original set of questions: after being assigned to work on knowledge graphs, I spent the majority of 2020 and 2021 researching knowledge engineering and data engineering to support this effort. Whether it was property graphs or hypergraphs, every implementation came with challenges. Leveraging data dictionaries and consolidated schemas failed to meet modeling requirements for disparate data sets. Additionally, a massive effort to modernize data management and governance paralleled these efforts as knowledge graph models require several different considerations such as data type and additional object logic. This array of challenges drove me to seek out upper-level (e.g., top-level) ontologies such as BFO.

The use of an upper-level ontology was ultimately the solution I chose. This choice was due to several considerations. The most important consideration and a challenge experienced by many data scientists and artificial intelligence (AI) engineers were this:

Humans do not want artificial intelligence (AI). Humans want machines that replicate useful aspects of human intelligence.

So how do you teach the equivalent of a speechless child to perform adult human tasks? One solution is to throw computational power and validated models at a problem to calculate solutions as quickly as possible. The other is to give the child the equivalent of adult heuristics to attempt to make adult-like shortcuts to answers. The drive to provide AI with shortcuts is why developing ontology right is crucial while simultaneously being extremely difficult.

My research on Basic Formal Ontology (BFO) helped me overcome several misunderstandings. I was unaware that in addition to being an international standard certified by the ISO, BFO established consistent, positive results in the medical and biological research spaces over the decades of its existence. These results included an accelerated research cycle for critical biomedical breakthroughs and building a culture to evolve the standard to new areas over the years. This use of a top-level rule system for building an upper-level ontology is preferable to a great ontology such as DBpedia or YAGO for several reasons, the biggest of which is that a customer rarely wants to maintain the contents of Wikipedia in their knowledge and data management systems. A customer ultimately wants to access their own essential knowledge quickly to iterate on decision-making heuristics. This clarification on knowledge graph requirements allows engineers and scientists to leverage machine learning for rapid iteration on models that best reflects the essential domain knowledge. Customers can then focus on the right questions and the most accurate scope for a decision.

This ontology system's history also proved helpful in my initial challenges. First, humans misuse words all the time. Specific and accurate language is critical for producing useful metrics when gathering data or engineering requirements. Additionally, when humans use the same words, they often use different implicit definitions. So not only must engineers monitor for consistency of word utilization, but they also have to monitor context. Next, human thoughts are rarely simple streams of logic, often emerging as spurts of rationale and circuitous statements that eventually provide a partial picture. So the engineer must consolidate multiple contexts into sets based on the words and their associated definitions. Finally (at least for this blog post), the engineer must ensure additional requirements or different projects do not shift words, definitions, or context sets. If there is a shift, provenance and legacy must be traceable within the ontology and the data artifacts connected to the ontology objects.

So not easy. Not easy at all.

The remainder of this blog will focus on a few of my biggest lessons learned for data engineering knowledge graphs using an adapted ULO.

Words Don't Matter. Situated Meaning Does.

It is beyond frustrating when requirements shift because an engineer allegedly "did not understand what" a customer "meant." The "what" here is a "word" that is a "thing" and a "thing" should be (at a minimum) unique within the context of the requirements discussion. Optimally, a word should "mean" the same thing throughout an organization, but this rarely, if ever, happens: this disconnect even happens between desks within established data teams. Furthermore, a new data set or a new fiscal year's vision may drastically shift a customer's essential domain knowledge dimensions. So the challenge is to establish clear language used and tracked consistently within the customer's knowledge development.

This problematic is where a ULO is extremely useful. To obtain this common knowledge development, an organization must agree to consistently structure their language on essential dimensions within knowledge and data management systems. After establishing the scheme that best fits a set of requirements, there may be an urge to jump straight into processing the data to fit a selected machine learning model. This course of action may skip essential steps such as characterizing the data within a metadata metamodel, mapping schema to a lineage of schemata, or expanding on the provenance of the data within a content management system. An ontology forces the engineer to align each data dimension to common "things" or terms. Common terms are the foundation of common understanding for an organization's decision-making models.

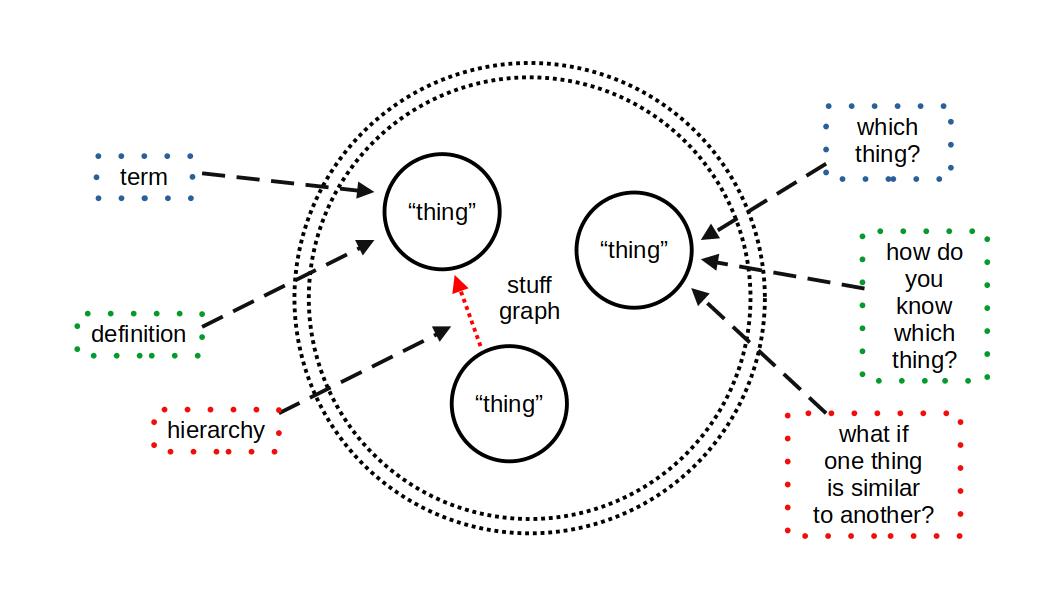

Once common terms are established and consistently used, there is still the challenge of knowing which things are which when one thing may be similar to another thing. A boat is a vessel that floats on water. A dingy is a boat that is small. A dingy is both a boat and a vessel, but the manner in which we distinguish these three terms is through structured definitions, which create hierarchical relationships between things and other things that are very similar. This "very similar" condition is often a single dimension of difference, allowing several branches to emerge from a common term that expands the typology and dimensionality of higher-level, more general things in the ontology. As a result, the data set features, or instances, connected to the ontology terms inherit this hierarchical structure.

So to recap:

- Term is just a distinct word for a common thing

- Definition is the term and its distinct description

- Hierarchy places the term and its definition into a tree which demonstrates inheritance between terms and their definitions starting with a universal "thing"

Ontology - Fundamental Elements

Ontology - Fundamental Elements

So a data dictionary is great for knowing how to define common terms, but an upper-level ontology can elevate your definitions to essential domain knowledge. Regardless of the system you choose, this ontology must be your ontology for all your things across all your data. We'll discuss this more in the next section.

Note: The universal "thing" is the term "Thing" which is a general Aristotelian starting point for an ontology, later used in the works of Linnaeus on taxonomy. As a result, BFO uses Aristotelian definitions to create the hierarchy for things in their ULO. This is later inherited by instances of the ULO things to which the data is mapped.

Consistency And Rigor Are Critical

As we demonstrated above with the boat example, a simple ontology can situate the meaning of terms to establish a common understanding of knowledge. But data, specifically highly-dimensional disparate data, requires a separation in ontology typology. To achieve consistent and rigorous knowledge modeling, you must be aware of the delineation between the ULO and an instance ontology.

An upper-level ontology is the main subject this blog is addressing. When properly implemented, the hierarchy of high-level, abstract things will contain archetypal properties that set the standards for each instance ontology and its entities. An instance ontology is a hierarchy of "real" things found in your data. Often an instance ontology is what people think of when they think about knowledge graphs and come in a few flavors (e.g., application, feature, etc.). Let's go through an example.

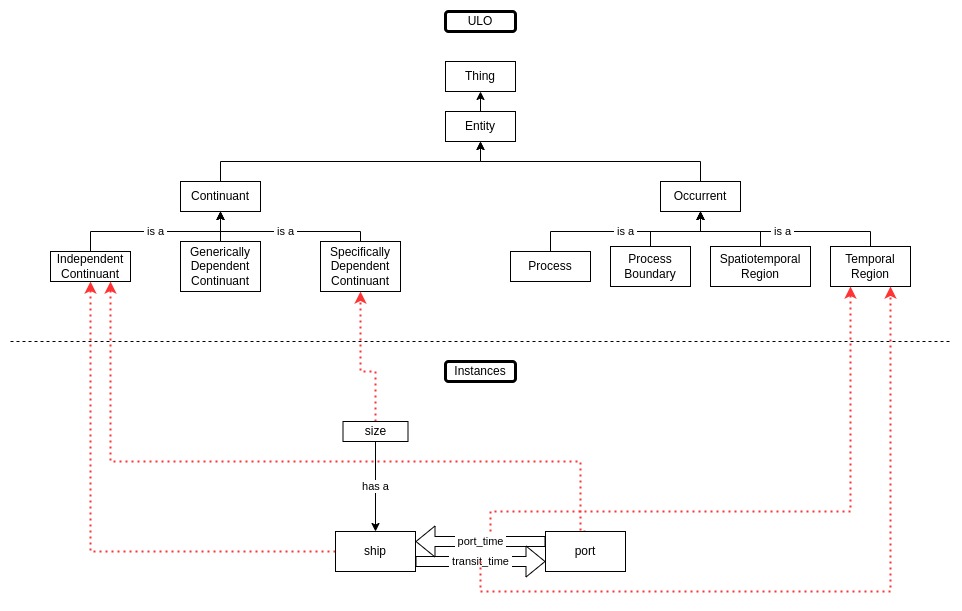

The top of our ULO is the universal "Thing." This universal thing is any "entity" that your organization's data may represent: an object, a process, a concept… anything. First, we have to delineate two types of entities from this universal entity: persistent entities regardless of a time frame and entities that only last for a specific time frame. From this point, we continue to branch out each of these entities. Entities that persist may do so on their own, may depend on other persistent entities to persist, or may persist beyond their original persistent state. Entities that persist for a limited time may only occur from start to finish, may occur at a start or finish, may occur in time or spacetime. None of these entities are "real": they are abstractions containing properties that real things manifest.

Let's say we get a new data set. The data contains fields on ships, port, ship size, time at port, and time of transit. We can quickly create dyads from this data at a basic network analysis level: [ship, transit_time, port]; [port, port_time, ship]. This modeling and exploratory data analysis would tell us a lot about transit and loiter times for these ships, potentially exposing valuable patterns and anomalies in the data for further analysis. But what happens when the analyst or scientist receives a new data set to expand the initial investigation? What happens when the same data comes in but the fields represent a different metric or collection method? What if the people who created this model leave and a new person needs to step in to integrate the new or altered data?

In honesty, these types of problems happen far too often, and non-ontology solutions work to resolve them. However, the machines we're trying to teach with these existing data solutions won't understand what we do with these data changes, resulting in humans overhauling models through prolonged retraining periods and undertaking new cycles of testing to explain and resolve the new outputs to the old. So humans should take as much care and effort as possible to foster some form of machine heuristics for understanding what things existed in the old data, what now exists in new data, and how one is related to the other.

This paradigm of linking instances to a ULO potentially resolves at least a few of these issues:

- Instances will consistently inherit data properties from the ULO entities. This inheritance allows the machine to maintain a foundational starting point for understanding differences in the data and its representations over time.

- The ULO acts as the connective tissue between new and old contexts for data. This context allows a machine to track shifts in the data dimension scope as new data interacts with other instances and their entities.

- The machine's ability to track lineage and provenance for instances lends extensibility for modeling entity dynamics across essential domain knowledge dimensions. The spaces of an organization's domain knowledge will shift over time, and a machine will need cumulative heuristics and the ability to use those heuristics to bolster decision-making when instances and data change.

ULO with Instances

ULO with Instances

The main point of distinguishing ULO entities and instances is to draw out the assertion that unless you set a data engineering standard for consistent and rigorous knowledge engineering, none of your data will accurately represent what we need it to represent across the organization. If you let your ULO model drift, you may as well not have an ontology at all. This system isn't a concern if your organization doesn't need an ontology for data-driven decision-making. However, if you're concerned with leveraging cumulative knowledge to grow your business, this delineation should be a primary data engineering focus.

The last note for the moment on the topic of consistency and rigor is that you can design your own ULO or adopt one. Still, you will ultimately need to observe and evolve said system if you want your organization's knowledge engineering to retain any value or drive any real impact for decision-makers.

An Ontology Is What Exists, Axioms Are How They Move

Structure and clarity are essential for the consistency and rigor of institutional knowledge. Ontology is a valuable way to bring out these connective knowledge qualities' explicit and implicit natures. Developing a ULO for an institution elicits several epistemological and axiological paradigms at varying scales. One question, in particular, is how intersectional practices and value judgments emerge from established socio-technical mores. This building of foundational knowledge aids decision-makers in the conception and tracking of metrics, assisting in selecting managerial criteria and optimal business direction. As a result, these data-driven processes must resolve the critical challenge of axiomatic ontological implementation.

Knowledge engineering, focusing on ULO development, must persistently resolve logical and functional misuse to optimize functional outcomes. All scientific disciplines make this challenge a primary research effort. Cartography suffers this same malady in that maps often misrepresent spatial phenomena to naively visualize dots, lines, and shapes geographically. Social network theory is often misused, resulting in massive "hairballs" of nodes and edges which lack fundamental dyadic meaning. In both cases, there is often a conflation of the underlying data scheme, schema, and/or ontology, leading to critical modeling errors. A ULO must account for these concerns and much more.

Once beyond the initial delineation between ULO and instances, universal and particular relational entity modeling must incorporate a system of axiomatic properties to outline and guide inheritance processes. In the case of many BFO standard and bespoke ontology systems, first-order or propositional logic is implemented to define properties for an entity as the context for relational conditions. The use of consistent logic grammars, symbols, and rules structured for communicating a state of an entity among other entities, allows an engineer to delineate unique things within the ontology model and aid in the ULO's application and extensibility.

In other words, the manner in which we define entities and contextualize their axiomatic properties produces heuristic-based data flows within the knowledge graph.

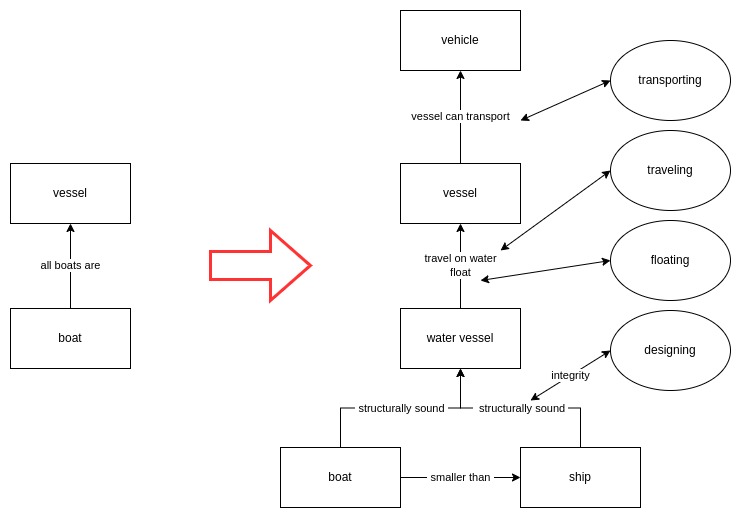

For example, all boats are a type of vessel. First, the engineers would have to achieve a consensus that this axiom is a provable fact about boats within the context of institutional knowledge. Knowledge engineers would then ensure that the continuant boat inheres from the continuant vessel within the instance graph through its definition and relational context.

Then one engineer asks, Is a boat still a boat if it is out of the water? It is an excellent question. How would a machine ascertain this: a set of environmental restrictions, naming convention, physical structure? These data elements may consist of both continuants and occurrents, which may exist elsewhere in the instance graph, but how do we know they are associated with the instance of boat and not an instance of some other vessel?

To assuage this inquisitive engineer, we need to give our boat enough axiomatic properties to ensure its uniqueness while reinforcing ULO rules of consistent inheritance and rigorous modeling. Using first-order logic, we'll generally assert:

- All boats are vessels

- Boat is smaller than a ship

- Boat can travel on water if properly designed

- Boat can float if structurally sound

So here, we encounter a few challenges. We have identified the task of defining a boat as a unique entity but realize there may be an intermediate water-based entity between vessel and boat (e.g., water vessel). There may also be an entity with properties above vessel that can help distinguish a boat out of the water (e.g., vehicle). The properties we have gathered so far are relevant but require augmentation of the instance graph with entities (e.g., ship, designing, traveling, structural integrity, floating). If all these axiomatic properties describe a water vessel, what makes a boat distinct now? Do the new distinctions still explain if a boat exists out of the water? Can we still teach a machine about a boat involving all the new entities with their properties?

Ontology Adjustment with Axiom Properties

Ontology Adjustment with Axiom Properties

This example is why AI engineers often abandon ontology approaches to machine learning: they are tough to build and maintain. However, the above processes and factors make using an ontology a powerful tool in training an AI agent if contextually implemented correctly. Humans use heuristic shortcuts to make decisions on highly complex matters. A ULO with consistent and rigorously enforced axioms is as close as we can get to providing a machine with similar shortcuts that are not an advanced form of rapid guessing. The computer will accept your axioms as facts about the entity, so consensus about entities and their properties is critical for enabling machine learning via knowledge engineering. When your data assets link to entity instances governed by an upper-level ontology, you have a powerful training tool for highly dimensional AI research efforts.

Conclusion

Ontology and knowledge graphs are not for everyone, but these structures are advantageous for those organizations that implement them correctly. Incorrect implementation will ultimately cause more harm than good in an organization's decision-making models. However, the gradual integration of data and information from data warehouses, content management, cloud architectures, and other information systems are steps in achieving truly dependable data-driven decision-making for an organization.

References

Basic Formal Ontology

International Organization for Standardization

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.