‘No-nos’ and ‘Know-knows’

Lessons Learned in Building Useful Knowledge Graphs¶

Posted by Joe Blankenship on 9 May, 2025

2019¶

In 2019, I was wrapping up yet another attempt at a PhD and in the process of moving to St. Louis to work on some pretty interesting geospatial data challenges. Around that time, a dear friend approached me with an even more interesting data challenge: one that overlapped with my interest in financial geographies, blockchain, and grey regulatory spaces. Needless to say, this changed my travel plans.

The challenge was not a trivial one: find and create connections between heterogenous, disparate data assets with very few clear dimensional overlaps. Aside from the more apparent spatial and temporal dimensions, there was no clear path to directly connect these assets into a network of meaningful relationships through which any person could easily understand and query for concise, human-readable answers.

The use of knowledge graphs was a requirement, but its need was not immediately clear. Many of the immediate questions could have been addressed with simpler, relational database approaches and some clever indexing methods. However, there was a distinct need that emerged from the consideration for a knowledge graph: a requirement for simple heuristic knowledge representations for a user that does not know about the nature of specific data structures, but desires the effects of particular data structures in their interactions with data systems.

When using dashboards or search tools, users simply want access to easily consumed, familiar heuristic artifacts they can quickly leverage in their daily tasks. Users want to see graphs they were trained to interpret, maps they have used to make critical navigation decisions, and search results in a language they know. This is why knowledge graphs were the right choice, but also the most challenging and brittle to build and maintain: certainly a great challenge for a data nerd such as myself.

So What is a Knowledge Graph?¶

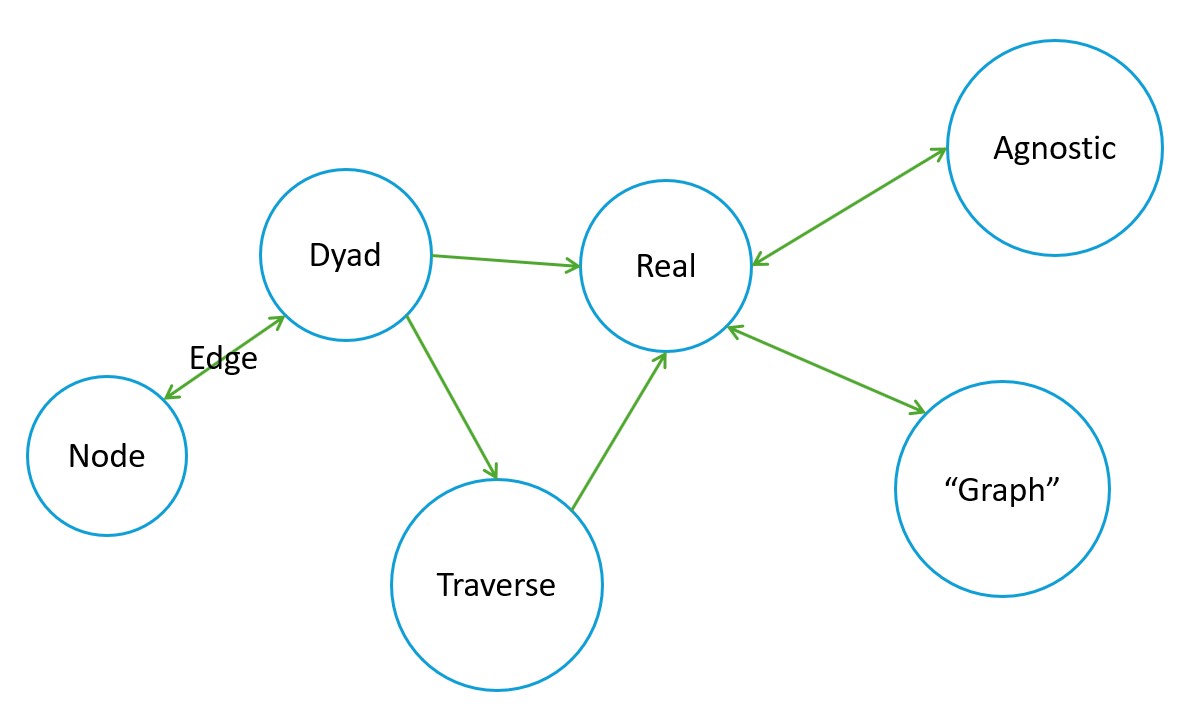

Borrowing from a dear friend and colleague, a knowledge graph is a platform agnostic data structure that constitutes a network of relationships. These relationships, represented using dyads, represent things that exist in the real world (e.g., there is data produced via a methodology that demonstrates that the thing can be observed). The dyad, a node-edge-node (or triple) data structure is the fundamental unit of analysis for a network of relationships that share either a node (most common) or edge (more bespoke e.g., hypergraphs). The goal of linking these dyads is to traverse the graph much like you would follow a trail. In this case, the trail is a logical, human-readable expression regarding the knowledge graphs nodes and edges to find real world instances that reflect that query pattern.

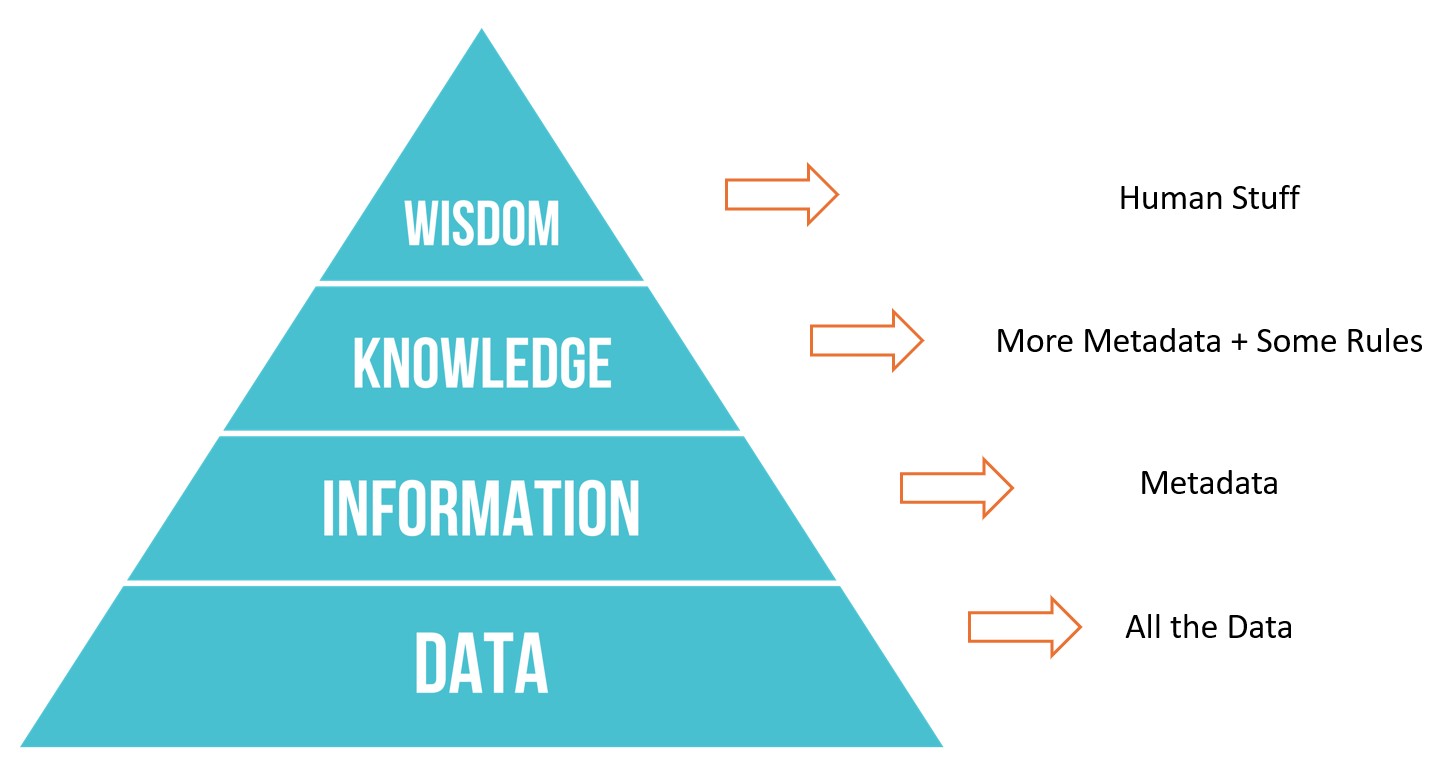

Knowledge graphs are (or should be) a cumulative data artifact. The knowledge graph should have a solid foundation of reliably modeled and managed data assets. There should then be sufficient information (e.g., metadata) available about the lifecycle and governance of these assets to make reproducibility possible under several circumstances including the original. Data and metadata should sufficiently bolster additional layers of logic and rules (e.g., metadata about the dyadic nature of your data dimensions) so that the production of knowledge graphs are consistently and rigorously possible.

However, these aggregate tasks are more easily said than done.

Do It Again!¶

With the knowledge graph challenge accepted, I then had to contend with all the complexities of making the solution make sense: a situation fairly common for data professionals in organizations where the managers are convinced they know your challenges as good, if not better, than you do. Taking disparate, heterogenous data assets and combining them into a knowledge graph is certainly doable with some creative data engineering and analytics; doing this twice with the same results was now the horrible task ahead.

If knowledge graphs are canonical representations of truth for a person, community, or organization, then it should be reproducible... “should be.” Each stage in the knowledge artifact production process is a series of opportunities to twist and adapt the truth by several sculptors with varying visions. Needless to say, without metadata and documentation to reflect these decisions, it becomes impossible to reproduce exact space-time instances of the knowledge graphs to the consistency and rigor needed for proper testing and longitudinal analytics.

All excuses aside, I did have to pursue at least a sufficient solution to this reproducibility challenge. The key goal was to constrain the amount of human error involved in expressing human “things” to a binary machine with no way to “understand expressions” of human “things.” I started with standards I previously worked with to structure metadata: WordNet[1] and schema.org[2]. These were good starting points: lexical standards of common expression for terms and their rough definitions as a result of their co-existence within a standard system of data structure and semantic rules.

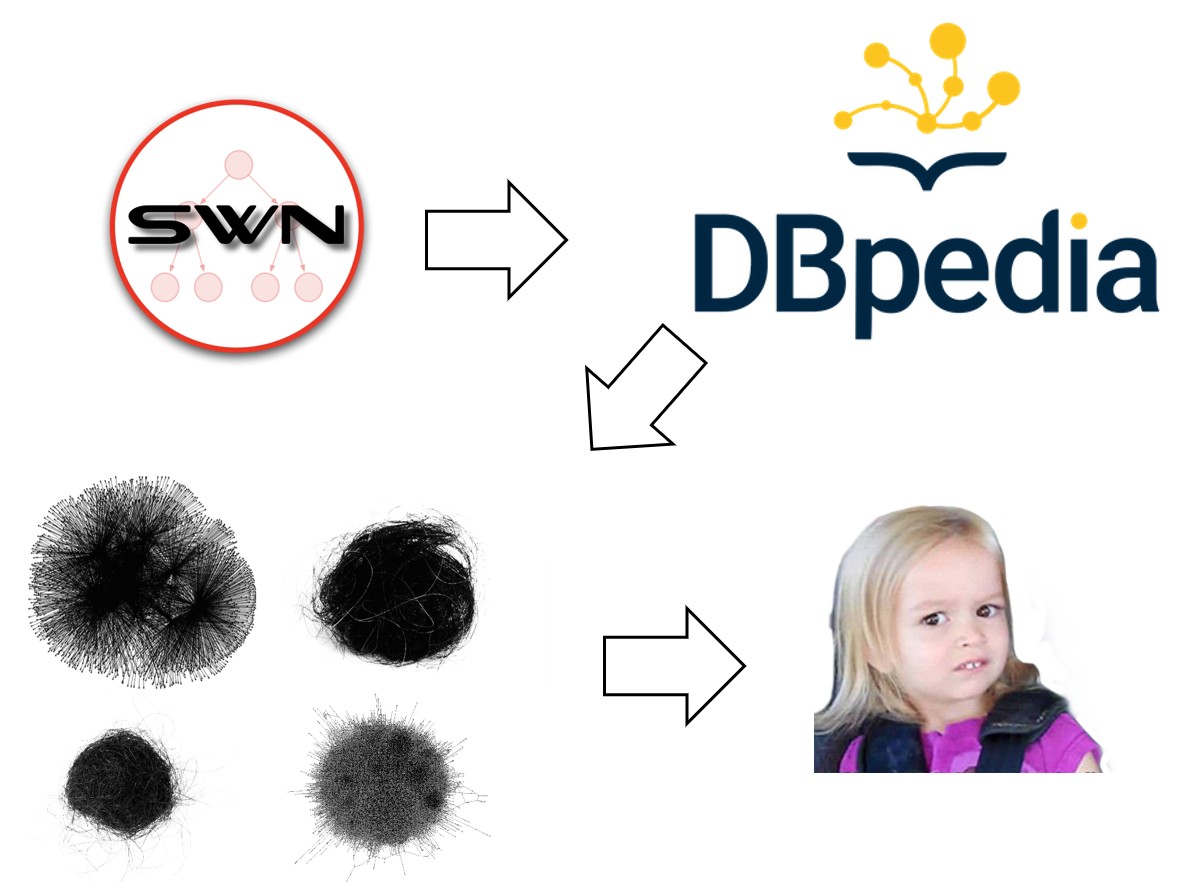

However, this approach was insufficient in many ways for a living knowledge artifact in need of constant extensibility and backwards compatibility. At this point, I also came across great ontologies like DBPedia[3] and YAGO[4]: collections of triples that came pre-built as a network of concepts and instances via well defined extraction methodologies. This approach had many advantages: mainly that I didn’t have to extract and build this myself, but also the data sources and methods used for extracting the triples were known and the methodology could be reproduced.

Unfortunately, this approach also fell short of expectations. The giant incoherent hairballs produced as a result of the great ontology processes were not easily interpretable or extensible. An engineer making this hairball work once is certainly feasible, but what do they do if a new “thing” that did not previously exist has to be added along with its instances? This is doable, but each engineer, scientist, and analyst may do this differently under different circumstances using different explicit and tacit knowledge: hardly the condition to ensure reproducibility in a consistent and rigorous manner.

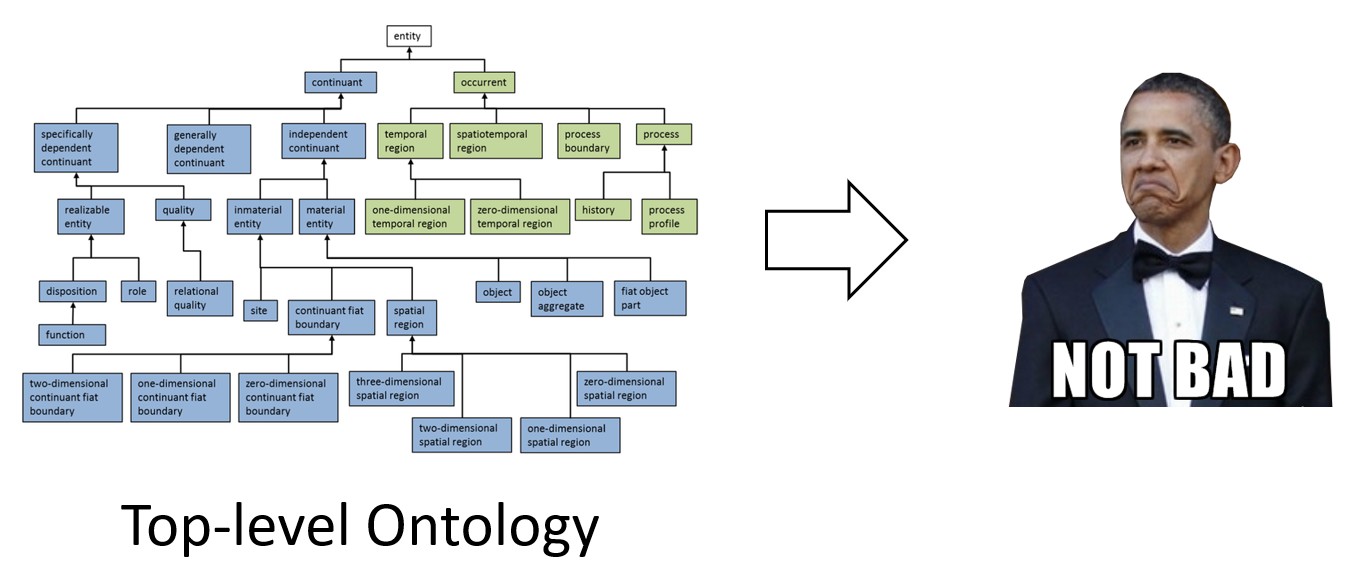

It was clear at this point that the production of the knowledge graph was not the challenge: it was ensuring that each human in the loop was playing by the same rules when engaging with these knowledge artifact procedures. As a result, I sought out a standard that enforced the use of rules to define knowledge itself and not merely define the engineering pipeline’s data structures that could produce a single knowledge artifact. After days of research, I found a standard that was previously used by the military to structure their bill of materials for fighter jets into a single, functional knowledge artifact. This discovery was the beginning of my long journey down the top-level ontologies rabbit hole.

Top-level Ontology and “You”¶

Standards in tech are great: there is literally a standard for each thing in tech and there are always new ones to supersede the old ones... each with a cult of personality convinced their approach is the superior approach. Needless to say, I usually proceed with varying levels of trepidation when deciding to build solutions around said standards as they often create as many issues you have to solve yourself as they answer regarding the initial challenge they purport to solve.

However, most top-level ontology (TLO) standards admit that it is nearly impossible to capture the world of knowledge in a single standard. As a result, their adaptability allows one to decide if these standards offered “better” utility than other knowledge artifact standards in the capturing of specific knowledge; potentially an answer that encourages reproducibility of these artifacts over time between groups of people with no previous knowledge of the other group’s activities. The artifacts of the standard have to encapsulate not just the knowledge itself, but had to reflect the human’s logic and rational for alignment and definition of knowledge while conveying the limitations of application for these artifacts in the process of data engineering any number of data product endpoints for an end user... not easy at all.

In the course of reviewing several top-level ontology approaches, I decided that the Basic Formal Ontology (BFO)[5] approach would be the most amenable to our processes and knowledge artifact goals. This system gives you a structure for defining knowledge using a hub-and-spoke approach to defining specific knowledge that encourages re-use and interoperability between specific knowledge clusters. The top-level abstract entities act as a guide by which people and their communities of practice could define their systems of knowledge without having to worry about overly specific naming conventions (something that makes interoperability between lexical databases very difficult) and instance co-population of “things” when defining their domain archetypes (something great ontologies do to their own convoluted detriment). Though this approach was the optimal one for our use case, it was still going to be a very challenging process for people to adopt and apply these expected practices.

With the inclusion of TLO practices, it is now feasible and possible to re-produce the same knowledge graph twice, but the reality of knowledge is that they are usually networks of networks that need to be reproduced asynchronously, but still maintain same canonical truth they represented the first time... here we go again.

2021 - 2024¶

In the process of rapidly iterating on knowledge graph solutions and the complexities that came with managing those types of teams (a blog for another time perhaps), it became clear that these data structures and architectures required much more than data to enable production, re-production, and reliability in its queries. After several trials, it was clear to me that though graphs via direct data assignment was easily achievable, there was a clear lack of lineage towards the human and machine context that allowed that particular instance of a graph to manifest in the specified data architecture. There needed to be a more clear understanding of the process for these solutions instead of just dealing with the endpoint solution itself.

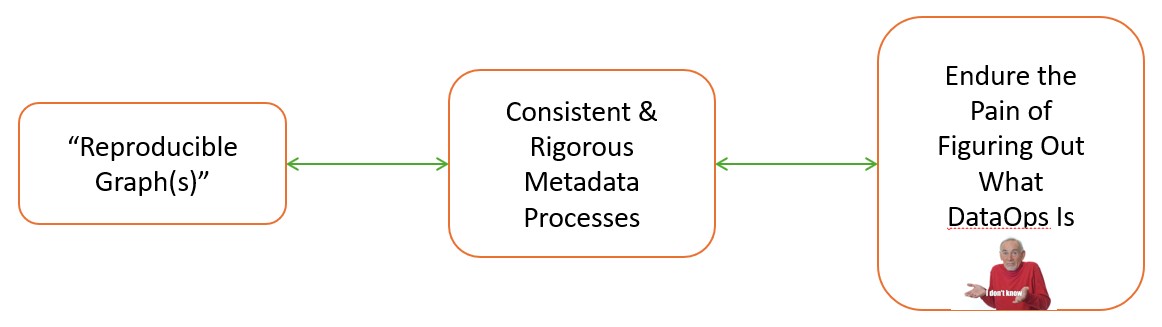

Knowledge graphs need context and focus because they are, or should be, rich representations of complex human systems (even in the most simple case). This situation implies that a consistent and rigorous strata of metadata is required between the data assets to be used and the knowledge graph to implemented: metadata and it processes are the critical aspect to the challenge of reproducibility and consistency. This realization unfortunately incurs a lot of very heavy, timely, and costly implications towards how the data systems that support knowledge graphs must adapt to implement and sustain this level of rigorous functionality. At this point, I came across a few articles on data operations (DataOps)... and I would never be the same again.

So What is DataOps?¶

Put simply, DataOps[6] are a collection of reminders to document and log all the things you were told to do with data systems and artifacts, know you need to do, but choose not to because it’s either too timely, costly, or because someone more senior told you “not to worry about it” (I’m sure there is a more formal definition, but this is practically what I’ve observed and seen from my experiences and have heard from many other data professionals). After consuming copious amounts of DataOps religious texts, I derived and focused on one key aspect of these texts: the production of consistent metadata object(s). To me, this understated aspect of dataops was the linchpin in producing any consistent data product more than once; especially one as complex as a knowledge graph.

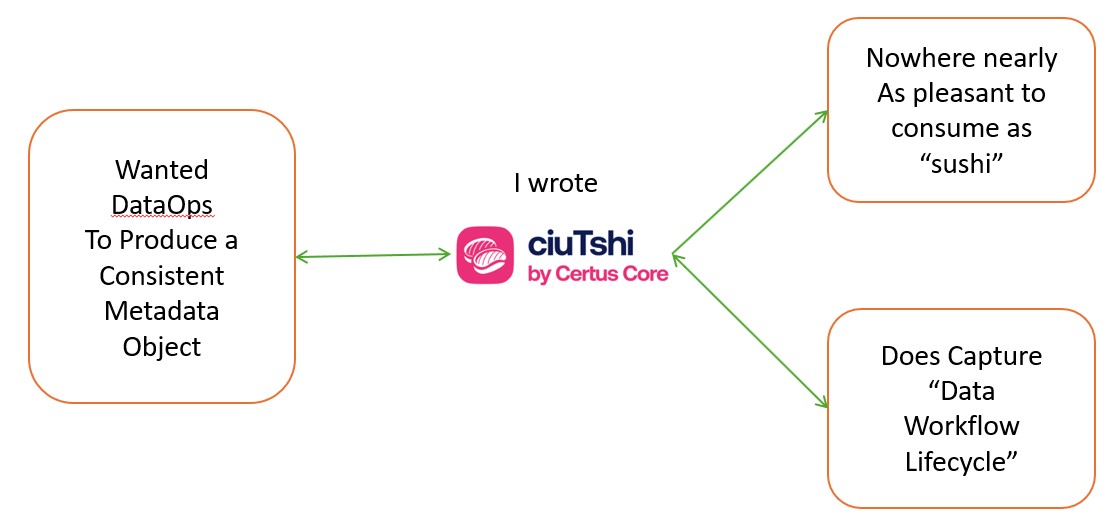

I proceeded to write what would become ciuTshi[7]: an adaptable data operations standard focused on production of consistent and rigorous metadata artifacts for each data asset within an organizations data architectures. Though this standard was yet another flat guideline for documenting what you know you should in the course of data engineering, it did present a consideration for what should be possible towards aggregate artifact integration via metadata structures. DataOps as a term and concept is a nice one, but still places the responsibility of adapting the organization’s bespoke data practices on the shoulders of the data engineers and other data professionals. Those professionals that embrace these challenges reap the rewards in more than the initial performance gains, but it is a protracted battle for implementing critical changes that many lose.

The goal of taking a general topic area (such as data operations) and tailoring it for a specific effect (such as ciuTshi) is still only a partial solution. The aggregation of these practices is not just to aggregate their artifacts: the goal of these efforts is to catalog the network of macro- and micro-procedures that represent the lifecycle of the data asset. This lifecycle is the story of the data asset and in my opinion is what makes DataOps necessary as a concept and not just an additional item on a data strategy checklist.

Large Language Models, Graphs, and More Problems¶

After a long exploration of knowledge graphs, ontologies, and data operations, it was clear that reproducibility was going to be a persistent challenge due to inconsistent practices and variations of systems (both technical and human) that foment variable conditions for choices on these matters. Data operations, with a focus on data management and data governance, aided the considerations toward these challenges, but was still not a panacea for reproducible data products from data assets and their metadata structures.

To further complicate this paradigm found throughout data engineering communities of practice, large language models (LLMs) emerged as a dominant factor in this time frame. At first, they were novel NLP models that pushed considerations on potential application spaces (something I would argue is still the case today). In terms of summarization and code completion, LLMs were absolutely useful and continue to be today. Though there are increasing numbers of applications backed by LLMs being developed today, there is still many questions pertaining to specific expert applications of these models for near-human practices.

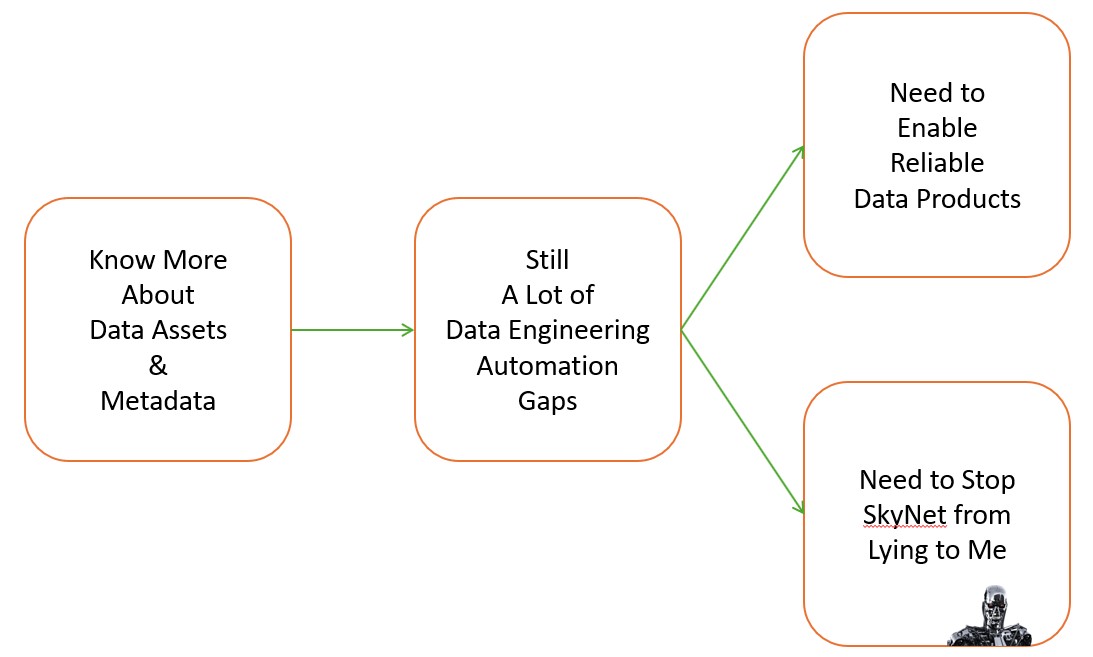

Until recently, my focus on use of these models was the (re)production of knowledge graphs from heterogenous, disparate data assets. This task initially involved systemic ability to explore and assess data assets to enable an automated data engineering workflow (something my colleagues were keenly focused on). This challenge required careful consideration on metadata structures and leveraging of these corpora to enable LLM functionality for enhanced data product pipelines. Unfortunately, this process exposed more automation gaps than it fixed, leading to further discussion on the actual utility of these LLMs in data engineering writ large.

So the focus on my efforts shifted back to the more practical question of how to enable reliable and consistent reproduction of data products without ceding all my work to a robot that is more likely to tank my systems through creative guessing than to take the position of talented solutions engineer.

GraphRAG and the Necessary Constraint of Language Models¶

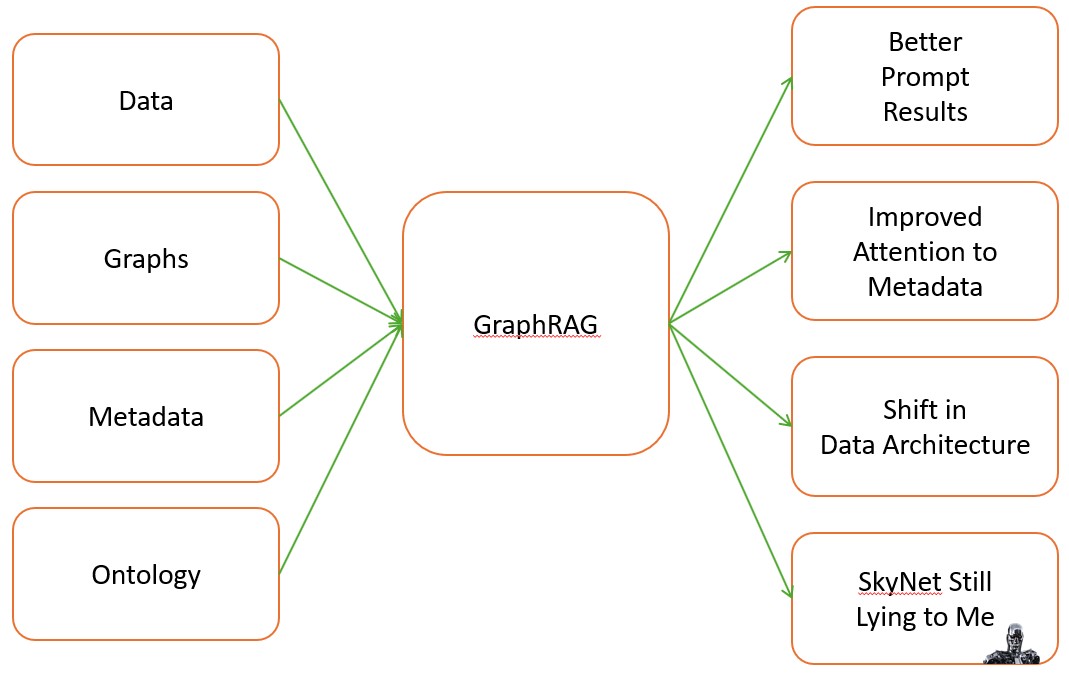

With the prevalence of LLMs came the immediate over-utilization of their artifacts. Having the consolidated surface of the Internet at your fingertips seems very useful at first, but general knowledge often leads to general results. Experts in need of expert knowledge systems still needed reliable, consistent responses from prompts that reflected their specific knowledge so that their communities and organizations could retain their specific data and knowledge value. This need drove the almost immediate search for the optimal tuning solutions around LLMs. From RLHF to RAG, the goal was to consolidate specific domains of knowledge as a priority response surface while retaining the broader utility of the LLM. Much like humans with a lot of general knowledge and some specific knowledge, it doesn’t take long before they begin to insert fallacious and biased notions into their responses: hallucinations that will persist so long as human artifacts are processed by binary machines.

The focus on ontologies did provide us some direct avenues of impact in this domain: using highly constrained graphs of canonical knowledge expressions to focus the LLM responses to that domain of knowledge. The notion that data, metadata, domain ontologies, and compliant knowledge graphs to data governance and ontology standards could fix hallucinations in these model responses is a solid and somewhat demonstrated solution to this challenge, but still suffers many of the challenges and constraints of other fine-tuning solutions. GraphRAG does result in better prompt results, enables a more engaged discussion on improved metadata standardization around ontology and other lineage mechanisms for data assets, and shifts how we consider utilization and implementation of data architecture to support these practices, but it does not solve all response issues for expert uses of these models.

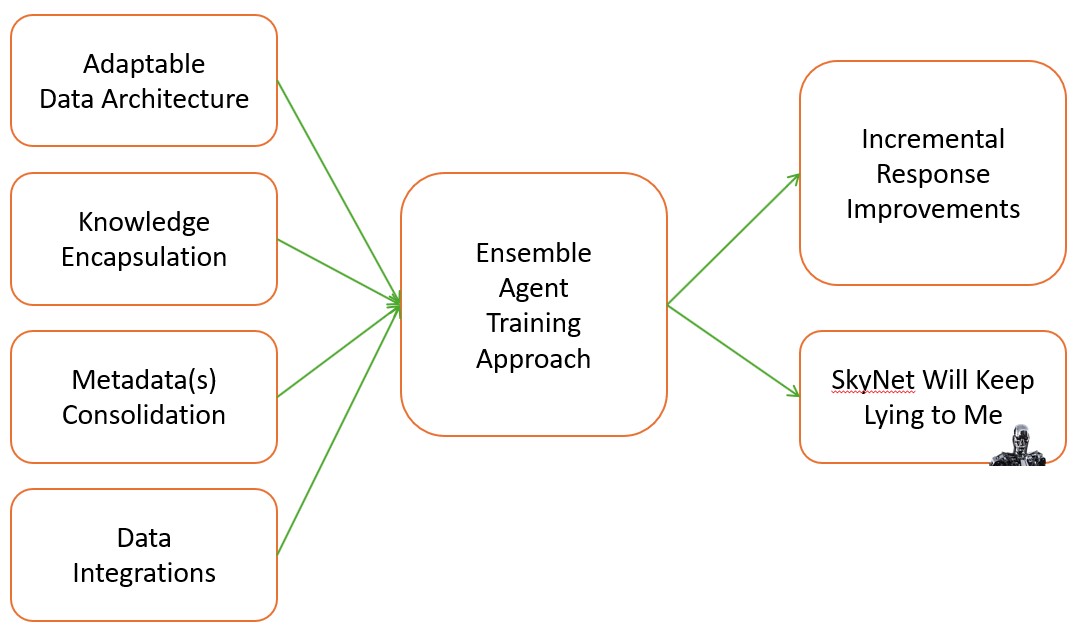

Bringing this back to knowledge graphs in the current era and their use as data products in training LLMs and as a data endpoint, there is as much to be said about what they are not and cannot do as can be said about their incredible potential. These highly human-readable artifacts can allow for a clear expression of the connections between data artifacts and the architectures that persist their utility and value. This ability to encapsulate human concepts for machine use is a critical aspect that bolsters their justified use in training LLMs and other GenAI models, but also makes them the most problematic if conceived and reproduced in way that completely contradicts their core purpose in your data operations. It is in the operations for careful and considerate metadata curation that makes these artifacts a no-no and know-know for data professionals: either the most confusing solution or greatest tool for expression they could get as a result of their hard work and collaborations. These human and machine considerations for function and outcomes makes the integration of knowledge graphs a mine field of choices that have no easy answer (regardless of the existing platforms and their rhetoric) and a plethora of unexpected risk and consequence; making documentation and logging of efforts toward training agents a holistic requirement for implementation of data and knowledge enpoints and not merely a result of their implementation.

I’m not saying all this work will keep SkyNet from lying to you sometimes, but incremental improvements to knowledge graph production standards and their metadata structures will certainly make dealing with their fibs more manageable.

A Future Trajectory¶

There is no denying the impact LLMs have made on the access and utilization of the seemingly endless collections of data and human knowledge. Much like the advances in search that came with Yahoo and Google, LLMs will irrevocably change the relationship humans have with technology and the world. For data and other technical professionals, knowledge graphs will continue to be a communication layer between these interstitial spaces of understanding bridged with LLMs to people via these technologies. LLMs and the metadata that feed these models are not going anywhere, so leaning in is the only direction for data professionals.

However, there is the present and future question of “how” we plan to lean in and deal with the consequences of these decisions. For my part, the focus on understanding how humans express knowledge, intuit that knowledge, and mediate understanding via machines for effect is where the challenges will persist and where there will be more questions than answers for years to come. I’ve certainly seen enough no-nos to have some idea of the know-knows that must take place to advance these data practices, but this advancement (as most things in our data disciplines) will depend heavily on humans around the world rapidly iterating and collaborating on these challenges together.

It is in this sentiment that I find so much hope for our collective futures... and maybe even SkyNet too.